On the website Ask Metafilter, I answered a question about dictionaries that I want to elaborate on here.

Metafilter user “Aswego” inquired:

Is there some super-secret linguistics resource that sorts dictionaries by prescriptivism/descriptivism? Either in a binary chart or along a spectrum? Which dictionaries are known to fit these categories, and which are known to straddle them?

The answer is easy: no, no such list exists. Why there is no such list is complicated. Let me try to explain.

Defining Terms

Prescriptivism is the assertion and enforcement of a specific set of rules by a person or institution. In dictionaries, prescriptivism means the dictionary explains there are language rules that should be followed and that certain forms or usages should be avoided. Usually these prescriptions and proscriptions are traditional and represent “received wisdom” that has been passed from teacher to pupil for a long time.

Descriptivism in a lexicographical context means that language behaviors and usage of language-users are examined by the editors. A set of characteristics that describe the language are derived from that study and then explained.

Here’s where it gets ugly:

Descriptivists sometimes describe prescriptivists as people who use circular logic or beg the question: “This rule is the rule because it is the rule.” They may also describe them as elitist and snobby.

Prescriptivists sometimes describe descriptivists as people who have no standards and are allowing morons to ruin the language, since, by not exclusively following the examples of those who call themselves grammar experts, we are allowing common people to influence how everyone should speak.

Another way to describe the difference, to use a popular example, is that a prescriptivist might say “Don’t start a sentence with hopefully.” Their argument would be that it has long been recommended to not do this and that one will be seen as uneducated. Historical or modern usage, no matter how frequent and widespread sentence-initial hopefully is, should not come into it. They may also try to use logic to prove English does not allow it, or that it does not mean what hopefully-users think it means.

A descriptivist might say, “Data and historical texts show that many writers and speakers of English have long used hopefully and other sentence adverbs at the beginning of a sentence to express something akin to the optative mood. It is, however, a skunked term that may draw criticism of one’s writing at the expense of one’s ideas. For that reason alone, you should avoid it.”

A skunked term is one that has been derided for so long that, even though it may be legitimate, even using it correctly may draw unwanted criticism.

That said, this isn’t the place for the prescriptivist vs. descriptivist debate (which has the potency of abortion or gun control debates in some circles), and I don’t want to turn this into a conversation about hopefully, either.

If you know the show, you know I’m largely a descriptivist, because I am, at heart, an empiricist. I look at the mass behavior of what speakers, editors, and writers do in their own texts, both professional and personal, and then use their behavior to guide my own writing and speaking habits, and to guide the advice I give others.

In any case, after some comments to Aswego’s question, he made an addendum:

I should probably clarify that I’m not looking to buy a dictionary, but that I was simply hoping for a (historical) survey of (American) English dictionaries. In other words, I’d be just as interested in information about an out-of-print 1890s dictionary as I would be a current one.

And since I get the “we’re all prescriptivists now” stance in modern dictionaries, I should probably have framed my question better with respect to that. To the extent that the narrative is true about the differences between Webster’s 2nd (1939), Webster’s 3rd (1961), and American Heritage (1969), were similar distinctions (whether framed in a descriptive/prescriptive way, or in a traditional/liberal way) being made about other dictionaries before that? Or in dictionaries focused on special topics?

Although Aswego amended his original question, it is good to reflect for a moment on the advisory role of dictionaries. I’ve provided links to texts and books at the end of this article which will help answer that question.

Another user suggested that prescriptive dictionaries were a sales and marketing choice:

The difficulty with having a prescriptive dictionary is that you’ll only sell one to each person, once. You can make a big sales song and dance about modern language usage, and maybe sell folks a new descriptive dictionary every decade or so.

I made a response there but have substantially updated it here:

Dictionaries are not based on corpora or descriptivist principles because such dictionaries sell at a higher volume. They don’t sell any better because the public usually does not understand the different compiling methods (nor would any lexicographer expect them to).

Here’s how marketing “corpus inside!” has gone when it has been tried. First you have to educate the public on what a corpus is. Then you have to explain what it does: it lets lexicographers analyze large bodies of specially coded written text to learn new things about words and language. Then you have to explain why that means folks should buy a corpus-based dictionary. It doesn’t really work in the short term, though perhaps with time over years or decades it could have an effect.

Marketing your dictionary as, “We’re super-prescriptivist hard-asses who will take no guff from those other laxicographers!” doesn’t work very well, either. It sounds like a hand will reach out of the book and smack you in the face.

In fact, what works best is: Be reasonably comprehensive, be reasonably cheap, and be easy to use. That describes many, many dictionaries. And it’s why marketing departments spend so much time — SO MUCH TIME — trying to differentiate their products from their competitors’ products.

Do Prescriptivist Dictionaries Even Exist?

So are there prescriptivist dictionaries? Not really. Dictionaries are based on descriptivist principles (largely using corpora and citation files as their source data) because that’s how dictionaries are made. If reference work is mostly prescriptivist, it is no longer a dictionary. It is a style guide or a usage guide and will be labeled and sold as such.

Dictionaries do often have usage panels (made of experts who give advice on frequently disputed language matters) and dictionaries do often include usage notes which can contain prescriptivist notions.

But usage notes usually serve to describe common debates (is the new meaning of beg the question okay?) and resolve common confusions (e.g., discrete vs. discreet, succeed vs. secede, procede vs. proceed), and not to demand certain linguistic behavior or to excoriate those who practice certain modes of speech or writing.

Prescriptivist usage and style guides do often demand and excoriate, even going so far as to call practitioners of certain speech and writing habits fools, idiots, uneducated, lazy, low-class, or contemptible, sometimes in those exact words.

I would reframe the original question:

What is the spectrum of reliability of the major English dictionaries? Which are more likely to give me advice that won’t be questioned by readers, customers, bosses, and professional colleagues?

The answer is that it’s a very thin range we’re talking about here. If the spectrum looks like this:

completely bad — poor — okay — good enough — good — perfect

then most mainstream English dictionaries in the US and UK fall between “good enough” and just to the right of “good.” You could pretty much buy any dictionary that includes entries for Internet, Obama, and all meanings for the verb monkey and get a good dictionary.

So Which Dictionary is the Best?

That’s like asking me which star in the sky is the best.

Here are my favorite non-specialty dictionaries for everyday use based solely on content of the latest editions. It would be a different list if we take into account one’s job, cost, portability, and paper vs. digital. And it would be still a different list if we were to list slang and dialect dictionaries.

Oxford English Dictionary. Super expensive so get access from a library. Best online. Slow to update. Totally impractical to carry around in paper form, though I’d love to see you try. Not very good on slang and Americanisms. Comprehensive with excellent historical perspectives, excellent etymologies, excellent use of citations for examples, and online you also get access to the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Two volumes. Not portable. Kind of expensive. Surprisingly, it’s not just a subset of the OED above. Instead, it has its own editorial team, is updated far more often, and includes many entries and meanings missing from the OED. It is not as American as I would like, but it has not ignored the New World, either.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. A solid, unabridged-like, reliable dictionary with superb etymologies (if that’s your thing) that are often very different from the etymologies in most other dictionaries (which have either simply passed along the same etymologies for decades without reassessing them, or they “borrowed” their etymologies from competitors). Its usage panel is an important differentiator, though often as not I find it to be summer camp for sticks-in-the-mud. By the way, AHD was a sponsor of the show last year, but if you’ve been listening for years, you know I’ve often recommended this dictionary before the sponsorship.

Steven Pinker and Dictionary Editors Weigh In

Since I first drafted this blog post, a conversation took place on the email list of the American Dialect Society about a very similar issue. Someone who compiled a list of court cases that cite dictionaries asked for a classification of dictionaries by their degree of prescriptivism.

Original question. Extract:

As you may know, Webster’s Third sharpened the debate as to whether definitions should tend toward authoritative pronouncements on what a word’s meaning Ought to be, or instead attempt to describe the way(s) a word is actually used by members of a speech community. I have coded for a range of specific dictionaries (plus a catchall category), and I wonder if there is some recognized taxonomy on this topic.

Response from Steve Kleinedler, Executive Editor of American Heritage Dictionaries. Extract:

Like our competitors, the editorial staff of the American Heritage Dictionaries crafts definitions based on citational evidence that shows how the word is used. The American Heritage Dictionary is NOT considered a “prescriptive” dictionary, although, like most cases, it does provide a small amount of prescriptive information (for instance, see the note at irregardless).

Response from Jonathan Lighter, editor in chief of the Historical Dictionary of American Slang. Extract:

When the Oxford American Dictionary appeared in 1980, its publicity claimed it “lays down the law about usage.” That’s the last truly prescriptive claim I can recall for any standard dictionary, and of course even at the time it was — shall we say? — exaggerated.

Response from Steven Pinker, Harvard College Professor of Psychology, Harvard University, and Chair of the Usage Panel, American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Extract:

I’ve recently looked at the history of the so-called prescriptive versus descriptive dictionaries. […] The distinction is almost entirely mythical, a meme ginned up by the media in the early 1960s and repeated endlessly for fifty years with no fact-checking.

Finding Out More

I compiled a list of a few resources which talk about the history of dictionaries from a variety of perspectives.

Chasing the Sun: Dictionary-Makers and the Dictionaries They Made by Jonathon Green. 1996. Green is a respected slang lexicographer who does an ample job of keeping this entertaining for the advanced lay reader. He writes a bit long and purpley for my taste but I forgive him. American dictionaries are not the focus but are given some treatment.

Oxford History of English Lexicography, two volumes, edited by A. P. Cowie. 2009. Expensive and academic but exhaustive.

"The Development of American Lexicography, 1798-1864" Janua Linguarum, Series Practica 37. 1967.

"American Lexicography, 1945-1973" by Clarence L. Barnhart. American Speech. Vol. 53, No. 2 (Summer, 1978). Top-notch scholar and scholarship.

"Lexicography in America : the history of a status conflict" by Bruce David Scott. 1978. I found it to be a passable summary of the debates as they were known in that era, despite its ridiculous use of the term "dictionary war."

The Story of Webster’s Third: Philip Gove’s Controversial Dictionary and its Critics by Herbert C. Morton. 1995. While on its way to explaining the brouhaha this new dictionary created, the book sufficiently and accurately explains dictionary trends leading up to it, especially since the second unabridged.

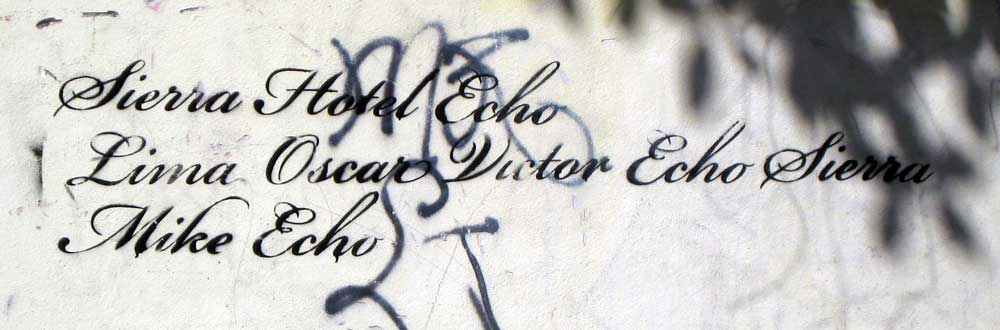

Photo by schmuela. Used under a Creative Commons license.

Jeez, is the Venn intersection of wordgame players and wayworders really solitary confinement?

Over a week now, and silence reins. Or have I used the site improperly?

s

Sharon, I’m afraid I don’t know much about the Scrabble dictionaries but they are not revised lightly. Keep in mind that the dictionary is part of the game. Working within its bounds is part of the rules, and part of what makes it challenging. It’s not a mistake that a word is missing.

A stable word set makes it possible for players to develop expertise against a static set of rules, and makes it possible for all matches in all eras to be considered the same game, and, therefore, be comparable.

I do think that all the Scrabble and Scrabble-like apps should have many, many dictionaries to choose from. Imagine a slang-only game, or one in which naughty words are allowed (or ONLY naughty words) or one in which only four-letter words could be used. There are a lot of possibilities!